There are three types of cells in the blood:

- Red blood cells (or erythrocytes): responsible for transporting oxygen.

- White blood cells (leukocytes): responsible for immune defense and protection against infections.

- Platelets (thrombocytes): responsible for blood clotting and, subsequently, for the repair (healing) of injured tissue.

Here, we focus on the platelets. They are much smaller than red and white blood cells. Their typical concentration is 150,000 to 300,000 per microliter of blood.

Their function can be briefly described as follows: when an injury occurs, platelets form a clot, which—together with the clotting factors in the blood—seals the damaged vessel.

Once the bleeding is stopped, the membranes of the platelets rupture and release their contents: hundreds of different growth factors.

These valuable and beneficial proteins have the ability to restore damaged tissue and initiate the healing process.

Why and for what purpose is PRP produced?

In 1970, it was first described that platelets could be easily concentrated and that this concentrate could be used medically to support healing. As with a standard blood draw, 10–40 ml of blood is taken, depending on the need, filled into a test tube that contains an anticoagulant (CaCl), and then centrifuged. Since the different components of blood (cells, plasma) have varying specific weights, several layers form in the tube.

At the bottom lie the red blood cells, which make up the majority of the cellular volume. Above that is a thin layer of white blood cells (known as the “buffy coat” in English), which is barely visible to the naked eye. Above this, the yellowish fluid layer—the blood plasma—is visible. At the bottom of this plasma layer are the concentrated platelets, which cannot be seen without a microscope. If this bottom part of the plasma is extracted, it results in platelet-rich plasma (PRP)—a fluid in which the platelet concentration is significantly higher than in regular blood.

In the upper part of the centrifuged tube, there are far fewer platelets—this part is referred to as PPP, short for “platelet-poor plasma,” although this term is rarely used in German-speaking contexts.

Images and illustrations

As a general rule: one-fifth of the drawn blood volume can be used as PRP. So, if 10 ml of PRP is needed, 50 ml of blood must be drawn. This also defines the practical limit of PRP therapy: in a person of average size and weight, around 150 ml of blood can be taken without causing circulatory problems or discomfort. Therefore, 30 to a maximum of 40 ml of PRP can be obtained per treatment.

For most treatments, much smaller amounts are sufficient (on average 20–40 ml), meaning the vast majority of known applications are easily feasible.

Production of PRP / Industry / Quality Control

As mentioned at the beginning, PRP is produced by drawing blood and centrifuging it. To simplify this process for treating physicians, the medical industry has developed kits (commercially available sets containing the necessary components for PRP production, except for the centrifuge). There are around 50 such kits on the market. Of course, a centrifuge must also be purchased. It usually comes with fixed settings, meaning the speed and duration of centrifugation are predetermined and cannot (or should not) be changed.

The kits include needles, syringes, and filtration systems that process the drawn blood by separating its components during centrifugation in such a way that the physician receives ready-to-use PRP in a syringe. This process is standardized.

However, it has become clear that due to the individual cellular and physical properties of blood, PRP is not always reliably produced. In other words: if you always do the same thing—i.e., centrifuge all blood the same way—you won’t always get PRP. Sometimes, the platelet concentration in the plasma is only equal to, or even lower than, that in normal blood.

Recent publications show that PRP is achieved in only about 65–70% of cases. In 10–15%, the concentration is roughly equivalent to that of whole blood, and in another 10–15%, the concentration is actually lower than that of normal blood.

This highlights the importance of verifying the outcome of PRP preparation before administering it to patients—because true PRP only results in about two-thirds of routine preparations.

Such verification is not complicated: there are small laboratory devices that can measure the platelet concentration in a plasma sample in under two minutes. If the concentration is adequate, treatment proceeds. If the platelet count is too low, re-centrifugation can increase the concentration.

For patients and consumers, this is important to understand: You should only agree to a PRP treatment if the platelet concentration is checked by the provider beforehand.

Applications of PRP

Below is an overview of the many possible applications of PRP.

Sports Medicine

PRP is often used to treat muscle and tendon injuries, including tennis elbow and Achilles tendonitis. Typically, three treatments are carried out at intervals of one to two weeks.

Orthopedics

PRP is used to accelerate healing after surgery or to improve joint function in osteoarthritis, relieve pain, and promote cartilage regeneration. Again, usually three sessions at one- to two-week intervals are recommended.

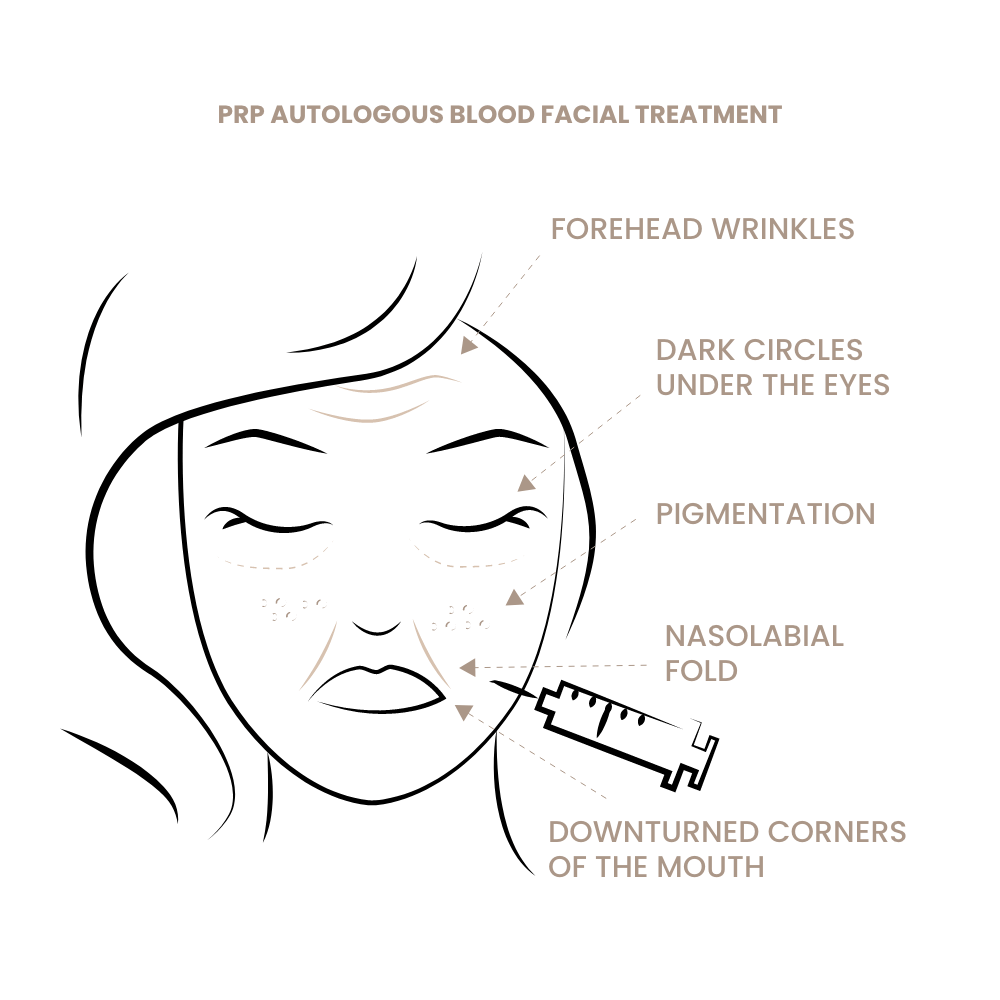

Dermatology & Aesthetic Medicine

Skin Rejuvenation (Vampire Lift)

The best-known PRP application is the Vampire Lift. Most practitioners inject PRP manually into the mid-dermis with a fine needle. However, studies show that a dual-layer injection yields the best results: first into the deep layer just beneath the dermis or lower dermis, and second into the upper or mid-dermis. Although more complex, this approach yields superior results.

Recommended: three treatments spaced three weeks apart (initial treatment + booster therapy), followed by maintenance every 2–4 months.

Scar Treatment / Acne Scars

PRP has shown good success in treating acne scars and other superficial skin irregularities or damage. Three initial sessions are recommended.

Sun-Damaged Skin

PRP has proven effective for treating sun-damaged skin. Depending on the condition, 3–5 sessions are recommended.

Impure Skin / Rosacea, etc.

PRP can also be used to address these conditions.

Fat Grafting / Lipofilling Support

The survival rate of transplanted fat is known to be highly variable. Adding PRP in a 5:1 volume ratio can increase survival by up to 25%. Another benefit: PRP softens the fat, significantly reducing lump formation—particularly important in facial fat grafting (under-eye circles, nasolabial folds, lips, hollow cheeks, etc.). This makes post-treatment shaping easier and helps avoid unwanted hardening.

Hair Growth – Women

PRP has long been used successfully to stimulate hair growth, especially in women post-menopause or with stress-related hair loss. Multiple treatments are usually needed to achieve results. In some cases, ongoing treatment is necessary—e.g., monthly or every two months.

If PRP is unsuccessful, nanofat treatment is a more effective (though more complex) alternative.

Hair Growth – Men

PRP is not always successful in treating androgenetic alopecia, but it’s still worth trying. We recommend five treatments at 3–4-week intervals. If there is no improvement after that, continuing is not recommended. If PRP is effective, ongoing maintenance treatments are advised to preserve the results.

If PRP is not successful, switching to nanofat may be the better option due to its higher success rate, despite requiring greater effort.

Note: Regenerative medicine alone is not enough to stimulate hair growth. Genetically miniaturized or damaged hair follicles also require supportive treatments such as vasodilators (Minoxidil, Botox) and anti-androgens (Finasteride, Dutasteride). See the chapter “Promoting Hair Growth Without Surgery” for more details.

General Surgery / Diabetes

Chronic wounds, slow-healing wounds, and diabetic ulcers have been successfully treated with PRP. In this case, PRF (platelet-rich fibrin) is typically used—PRP is coagulated into a gel or cream that can be applied to the wound and remains in place more easily.

Dentistry

PRP is used in dental procedures such as implants, root canal treatments, and jawbone reconstruction. It can promote healing, reduce infection risk, and support new bone formation. It’s also used in periodontal therapy to stimulate tissue regeneration.

Ophthalmology

PRP is used to treat certain eye conditions such as dry eyes, corneal ulcers, and conjunctivitis. It can support healing, reduce inflammation, and promote tissue growth.

Gynecology

PRP is used to treat vaginal atrophy, pain during intercourse, and urinary incontinence in women. It can stimulate vaginal tissue regeneration, improve tightness, and reduce dryness. As a stronger alternative, nanofat may also be used.

Summary

The possible applications of PRP are indeed diverse. They overlap considerably with those of nanofat treatment. However, nanofat is significantly more effective, although it involves a much more complex and time-consuming process.